TheFarmersDigest

The Farmers Digest

Jun 5, 2025

Editor

Chris Pigge

Editor

Miles Falk

Mastering the Mechanics: Advanced Rotational Grazing Strategies

Moving cattle between paddocks seems simple enough, but turning rotational grazing into a profit-driving system requires understanding the details that separate good graziers from great ones. While any rotation beats continuous grazing, fine-tuning these systems can dramatically boost your bottom line and pasture health.

Getting Your Forage Math Right

Knowing how much grass you have determines everything else in your grazing system. The basic calculation is straightforward: take your total forage per acre, multiply by your acres, then divide by what your herd eats daily. This tells you how many days that paddock will feed your cattle.

But first, you need to figure out how much forage you actually have. The grazing stick method is the most practical way for most farmers. Walk your paddock taking measurements every 30-50 steps—you need at least 30 measurements per paddock to get accuracy. Measure the actual leaf height of the grass, not the tall seed heads that cattle won't eat.

Each inch of grass height represents different amounts of dry matter depending on your grass type:

- Cool-season introduced grasses (fescue, orchardgrass): typically 100-150 pounds per inch

- Cool-season native grasses (wheatgrass, needlegrass): typically 75-125 pounds per inch

- Warm-season native grasses (big bluestem, switchgrass): typically 150-200 pounds per inch

So if your fescue paddock averages 8 inches tall at 125 pounds per inch, you have roughly 1,000 pounds of dry matter per acre. But you can only use about half without hurting regrowth, leaving you 500 pounds of available forage per acre.

A 1,400-pound (635 kg) cow eats about 56 pounds (25 kg) of dry matter daily—roughly 4% of her body weight. Your herd of 50 cows needs 2,800 pounds (1,270 kg) of forage every day. If your 10-acre paddock has 500 pounds of available forage per acre, you have 5,000 total pounds available. Divide that by 2,800 daily needs, and you get about 1.8 days of grazing—time to move soon.

Here's where most people get tripped up: you can't use all the grass. Taking more than 50% stresses plants and hurts regrowth. Intensive systems can push to 70% utilization, but only with perfect timing and longer rest periods. When in doubt, be conservative—a slightly undergrazed pasture recovers faster than an overgrazed one.

Working With Nature's Seasons

Grass doesn't grow the same all year, and your grazing needs to adapt accordingly. Spring brings explosive growth that can outpace your herd's ability to keep up. During this flush, you might need to move cattle daily just to keep grass from going to seed. Don't worry about "wasting" grass—you're managing for the whole season, not just one week.

Summer heat slows cool-season grasses to a crawl. Those 21-day rest periods that worked in May might need to stretch to 45-60 days in July. This is when warm-season grasses shine, providing quality forage while your fescue and orchardgrass take a break.

Fall brings another growth spurt for cool-season species, but now you're preparing for winter. Leave more residue in your final grazing—taller stubble helps pastures bounce back faster next spring and provides better winter protection for the root system.

Don't fight the calendar. In the Midwest, expect 40-50 day rest periods most of the season, stretching to 90-100 days in hot, dry conditions. Cool-season grasses need those longer breaks during summer stress periods.

Water: Your System's Bottleneck

Poor water placement kills more rotational grazing dreams than bad fencing. Cattle won't walk more than 800 feet (244 meters) to water regularly, and utilization drops significantly beyond 200 feet (61 meters). Plan your paddocks around water access, not the other way around.

A big cow drinks 25-30 gallons (95-115 liters) daily in hot weather. Multiply that by your herd size and add 20% for safety. Your 40-cow herd needs 1,200+ gallons (4,500+ liters) daily, but not all at once. Cattle are social drinkers—when one goes, they all go. Size your tanks and flow rates accordingly.

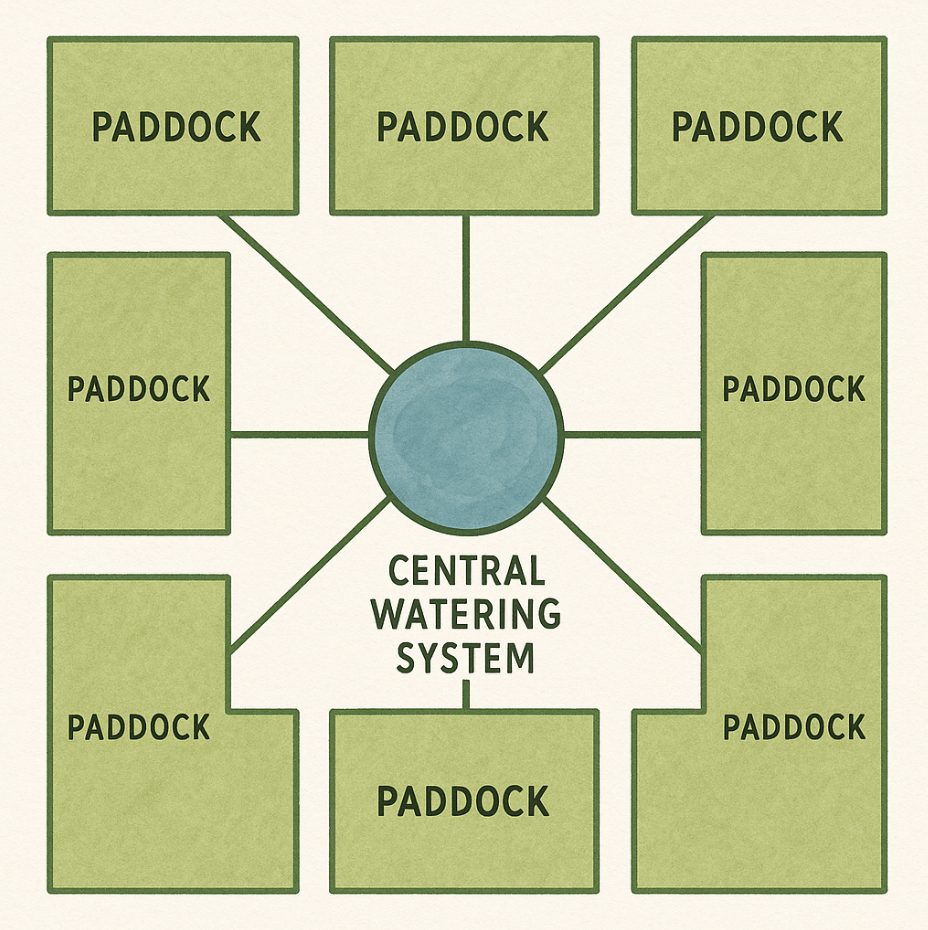

Three water system approaches work well. Centralized systems put water where multiple paddocks can access it, though this limits your paddock flexibility. Mobile systems move water to the cattle, giving maximum flexibility but requiring more daily work. Most successful operations blend both approaches—permanent water in high-traffic areas with portable tanks for flexibility.

Skip the engineering headaches. If water flows uphill from your source, you have pressure. If it doesn't, you need a pump or elevated storage. Keep it simple and keep it working.

Timing Your Moves

When you move cattle matters almost as much as where you move them. Many successful operations move once daily around midday when cattle are naturally less active. Some push for twice-daily moves for maximum precision, but most find the extra labor doesn't justify the marginal gains.

Daily moves create healthy competition in your herd. Instead of wandering around picking the best bites, cattle eat more uniformly when they know the buffet closes soon. This behavior helps control weeds and improves overall forage utilization.

Watch your grass height for move signals. The "Take Half, Leave Half" rule keeps it simple—when you've grazed half the available forage, it's time to move. For most grasses, this means leaving 3-4 inches (7.6-10 cm) of stubble during peak season, increasing to 4-5 inches (10-12.7 cm) during summer stress.

Don't overstay your welcome. Seven days in one paddock is generally the maximum before grass starts regrowing and cattle start selectively regrazing new shoots. Move before this happens.

Stocking Rates That Actually Work

Rotational grazing lets you run more cattle than continuous grazing, but how many more depends on your management intensity and grass productivity. Well-managed rotational systems typically support 20-30% higher stocking rates than continuous grazing while maintaining animal performance.

The animal unit month (AUM) system standardizes everything to a 1,000-pound (454 kg) cow with calf. Your 1,500-pound (680 kg) bulls count as 1.5 AUs, while 700-pound (318 kg) yearlings count as 0.85 AUs. This keeps your math consistent regardless of what you're running.

Start conservative and build up. If your continuous system ran one cow per 3 acres, try 1.2-1.3 cows per 3 acres with rotation. Monitor body condition and pasture health closely. You can always add cattle next year, but fixing overgrazed pastures takes multiple seasons.

Stocking density—animals per acre right now—differs from stocking rate. You might run one cow per 5 acres overall (stocking rate) but concentrate 50 cows on 10 acres today (stocking density of 5 cows per acre). This concentration creates the trampling and uniform grazing that makes rotational systems work.

Monitoring That Makes Sense

Successful graziers develop an eye for grass, but numbers keep you honest. Measure the height of grazed and ungrazed plants of the same species to calculate utilization. If ungrazed grass stands 12 inches and grazed grass averages 4 inches, you've used 67% of the plant height—probably too much for sustainable management.

Different grasses tolerate different grazing pressures. You can take 80% of the height from wheat grasses and bromegrass, but big bluestem shouldn't lose more than 75%. Learn your key species and their limits.

Stubble height measurements work just as well as complex utilization calculations. Measure what's left after grazing rather than calculating what was removed. Higher fall stubble heights—4 inches (10 cm) or more—help pastures start stronger next spring.

Photo monitoring captures changes over time that daily observation might miss. Take pictures from the same spots each season to track improvements or problems. Your phone works fine for this.

Making the Numbers Work

Rotational grazing infrastructure costs vary dramatically with scale. Small operations under 100 acres (40 hectares) might spend $70 per acre ($173 per hectare), while large operations over 400 acres (162 hectares) can get by with $10 per acre ($25 per hectare). Temporary fencing, basic water systems, and used equipment help control startup costs.

The payback comes through extended grazing seasons, reduced feed costs, and higher stocking rates. Each extra day on pasture versus feeding hay can save $1.50+ per cow daily. Stretch your grazing season 30 days and save $4,500+ annually on a 100-cow herd.

Labor efficiency makes or breaks intensive systems. Cattle trained to rotational moves come running when they see you, making moves quick and easy. Simple infrastructure—wide gates, smooth fence corners, and logical cattle flow—reduces daily work.

Technology helps, but don't overcomplicate things. A grazing app to track moves beats a notebook that stays in the truck. GPS helps measure paddocks accurately. A grazing stick costs $30 and works every time.

Adapting to Your Place

No two farms are identical, and no single system works everywhere. Elevation, climate, soil type, and grass species all influence what works best. Start with basic principles and adapt them to your situation.

Your rotation frequency depends on your grass and goals. Fast rotations with daily moves provide maximum control but demand more labor. Slower rotations with weekly moves offer good results with less daily management. Most successful systems fall somewhere between these extremes.

Drought changes everything. In dry years, extend rest periods and reduce stocking rates early rather than waiting for grass to disappear. Flexible systems adapt to conditions rather than fighting them.

The Real-World Bottom Line

Rotational grazing succeeds when it matches your management capacity and economic goals. Perfect systems that burn you out don't work long-term. Simple systems you can maintain consistently beat complex systems you abandon after two seasons.

Start with what you can manage and build from there. Divide one pasture in half and rotate between the halves. Add complexity gradually as you gain experience and see results.

The fundamentals never change: match grass supply to cattle demand, provide adequate rest for regrowth, ensure easy water access, and monitor results constantly. Everything else is details that you'll figure out through experience.

Your land will tell you what works. Listen to your grass, watch your cattle, and adjust accordingly. The best rotational grazing system is the one you'll actually use consistently, season after season.

References

Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. "Rotational Grazing Systems for Cattle."

Farm Advisory Service. "Supplying Water to Rotationally Grazed Beef Cattle."

Kentucky Forage News. "Water and Rotational Grazing."

Oklahoma State University Extension. "Stocking Rate: The Key to Successful Livestock Production."

Pasture.io. "Rising Plate Meter Equation."

Pennsylvania State University Extension. "Grazing Residue Height Matters."

Pennsylvania State University Extension. "How to Make Rotational Grazing Work on Your Horse Farm."

Province of Manitoba Agriculture. "Animal Unit Months, Stocking Rate and Carrying Capacity."

Riemer Family Farm. "How We Move Beef Cattle on Pasture Every Day."

ScienceDirect. "Stocking Rate - An Overview."

South Dakota State University Extension. "Using the 'Grazing Stick' To Assess Pasture Forage."

University of Florida IFAS Extension. "Grazing Methods Impact on Forage Cattle Production."

University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. "Understanding Stocking Rate in Pasture Systems."

University of Minnesota Extension. "Grazing and Pasture Management for Cattle."

USDA Climate Hubs. "Rotational Grazing for Climate Resilience."